Figure

1. Farmer at work in Pinar del Río.

Figure

1. Farmer at work in Pinar del Río.| Part I: Background | Part II: Traditional Music | Part III: Popular Music |

| Geography | Folk Music | Mambo |

| Politics | Instruments | Salsa |

| Economy | Performers | |

| Culture | ||

| Bibliography | ||

| Webliography |

Cuba is a very mountainous island with ranges covering approximately 25 percent of the country. There are three separate mountain systems: the oriental, the central, and the occidental. These ranges supply Cuba with many different kinds of industrial and agricultural products, which will be discussed in detail in each section.

The oriental system is also known as the Sierra Maestra. This system is the most extensive and complex. This system is located in the southeast and spans the provincias of Granma and Santiago de Cuba. The highest point in Cuba, the Real del Turquino Peak, is the Sierra Maestra. It reaches to 6,746 feet.

The Sierra Maestra yields many different types of goods. The heavily forested range produces many different types of wood such as cedar, mahogany, and ebony. The slopes produce large coffee crops. Besides farming, the mountains are mined for valuable ores and stone. The hills of the Sierra Maestra yield iron, copper, chromium, asphalt, and marble.

The occidental system is also called the Cordillera de Guaniguanico. These low hills are located in western Cuba in the provincia of Pinar del Río. There are two major peaks in this range: the Sierra de los Órganos and the Sierra del Rosario. The latter peak rises to 2,293 feet.

The Sierra de los Órganos has vast limestone deposits. Huge oak and pine forests cover the rest of the Cordillera. One unique resource is the mineral springs that occur on the fault lines of the Cordillera.

The main inland waterway of Cuba is the Cauto River, which stretches over 230 miles in the southeast. The Cauto's source is in the Sierra Maestra and flows through the Granma and Santiago de Cuba provincias. The Bayamo, Salado, and Contramaestra rivers are tributaries of the Cauto. Like the Sierra Maestra, the Cauto provides irrigation for crops of rice, tobacco, and sugarcane. The fertile land surrounding the Cauto River supports cattle farming.

Land forms are not the only thing in Cuba that is diverse. The flora and fauna of Cuba is extremely varied. There are nearly 8,000 species of plant life on the island. Although there are many species of plants, much of the original vegetation has been removed to make way for agriculture and industry. The government instituted extensive reforestation after the destruction of forests for economic gain.

Timber is an export of Cuba. There is a small supply, but the quality is exceptional. Mahogany, ebony, and pine are used for timber. While these trees produce timber, two trees in particular that are associated with Cuba have nothing to do with economics. The royal palm is the national tree of Cuba. It reaches heights of 50 to 75 feet. The second tree is the cork palm. This tree is very rare and considered a "living fossil." The island's warm climate can produce large amounts of citrus fruits. Traditional fruits such as lemons, oranges, and grapefruit grow alongside such exotic ones as papayas and bananas. Tobacco and mangrove are cultivated in the lower regions.

The wildlife of Cuba is equally impressive. Living in or around the water, there are over 4,000 species of mollusks, 500 species of fish, and 35 shark species. There are also 7,000 insects. Of the 300 species of birds on Cuba, only about one-third are indigenous. Some of these are the flamingo, royal thrush, and the nightingale ("The West Indies," 3).

Land animals are abundant in Cuba. Many different kinds of reptiles grace the varied landscape of Cuba. The tortoise and hawkbill turtle reside in the waters, the rivers are home to the mud turtle, and two types of crocodile live in the marshes.

Two endangered species reside in Cuba. The first is the solenodon. This small ratlike creature is nearly extinct in Cuba. The only place it continues to survive in is the Holguín provincia. The Cuban government protects the solenodon. The manatee is another threatened species. Boats often injure the manatees that swim in shallow waterways. The government often protects these aquatic mammals as well.

Cuban customs and traditions are similar throughout the island, making a regional distinction based on culture impossible. It is better to categorize Cuba by geographical standards. There are five main areas of Cuba, which are sectioned again into provincias.

The Occidental (Western) region is the largest land area in Cuba. Although most of this region is plains, the Cordillera de Guaniguanico adds variation to the flat landscape. The Occidental region houses 40 percent of Cuba's population along with the capital city, Havana. There are five major provincias in this division: La Habana, Pinar del Río, Matanzas, and parts of Villa Clara and Cienfuegos.

La Habana is located in the west-central area of Cuba. It is 2,213 square miles. The provincia is densely populated because of the capital city, Havana. The northern coast is dotted with beaches and the lovely La Habana Bay. Mangrove forests cover the swampy southern coastline. Along with the agricultural yields that are typical of Cuba, La Habana has a thermal-nuclear power plant and an industrious shrimp port in the southwest.

The capital city, Havana, is actually composed of many smaller, older cities: Havana, Marianao, Regla, Guanabacoa, Santiago de las Vegas, and Santa María del Rosario. Havana is the economic center of Cuba. It has many industrial and agricultural resources. Root crops, livestock production, coffee, and plantations abound in the farmland. Within the city proper, there are factories for shipbuilding, food processing, textiles, chemical, and automotive production.

Figure

1. Farmer at work in Pinar del Río.

Figure

1. Farmer at work in Pinar del Río.Matanzas is 4,625 square miles. It is known for two things in particular: tourism and sugarcane. Matanzas City is a major center for tourism. Cárdenas and Matanzas City are the largest sugarcane ports in Cuba. Like La Habana, Matanzas has mangrove crops in the swampy areas in the south.

Up until 1976, Villa Clara was part of Las Villas. Now, this 3,117 square mile territory is a booming economic area. Agricultural activity consists of tobacco, sugar, rice, fruit, black beans, and cattle. Villa Clara is also an industrious city. There are sugar refineries, foundries, sawmills, distilleries, and leather factories. The nearby hills are mined for gold, asphalt, and barite. If not all this was enough to make a thriving city, there are also two heavily traveled ports: Caibarién and La Isabela.

Santa Clara, the capital of Villa Clara, is worth mentioning because of its rich history. The city is located on the top of coral hills reaching 367 feet above sea level. Families fleeing pirates attacks in Remedios formed the city in 1689. There are some legends stating that Columbus mistook Santa Clara for Kublai Kahn, the Mongol emperor.

One of the smaller provincias is Cienfuegos, totaling only 1,613 square miles. Like many of its surrounding territories, Cienfuegos produces sugarcane, tobacco, and rice. The fertile coastal plains also produce henequen. Ropes and rugs are made from the fibers of this plant. Due to the superb harbor created by the Cienfuegos Bay, this small provincia has one of the best export and fishing ports in Cuba. The crowing glory of the area is the Sierra de Trinidad rising 3,793 feet above the plains.

While the Occidental region is the largest in area, the Central region is the largest in tobacco production. The Manacas and La Trocha plains provide the perfect landscape for growing tobacco. The provincias Sancti Spíritus and Ciego de Ávila and the archipelago of Sabana-Camagüey are the best know of this region.

Figure 2.

The principal church in Sancti Spíritus.

Figure 2.

The principal church in Sancti Spíritus.

When Las Villas was divided in 1976, Sancti Spíritus (see Figure 2) was created along with Villa Clara. However, Sancti Spíritus received a smaller portion of land adding up to 2,588 square miles. The plains along the coastline become the Sierra de Sancti Spíritus in the southwest. In 1954, Jatibonico struck oil. It has remained Cuba's main petroleum producer since. In addition to oil, the hills near Formento are mined for manganese and serpentine.

The Ciego de Ávila provincia is 2,668 square miles. Large cays, which are low coral reefs, spot the northern coast. The northern part of the region produces coffee and cocoa. Industry in Ciego de Ávila City consists of sawmills, bottling plants, refineries, and distilleries.

The next geographical territory is the Camagüey-Maniabón region in the southeast. This area is situated on an ancient piece of land that has been almost completely eroded. This land is called a peneplain.

The territory of Camagüey is the most prominent of this area. It is the largest provincia in Cuba at 6,174 square miles. It was original named as Puerto Príncipe in 1879. It grew to become the leading cattle and sugar producer. These goods helped to establish Camagüey as an economic center. Its poor harbors would not have been able to keep the provincia alive.

Las Tunas is also located in the Camagüey-Maniabón region. Las Tunas is 2,544 square miles. It was a part of the former Oriente provincia until 1976. Produce includes tobacco, corn, beans, peanuts, and cassava. Cedars are grown on plantations for timber.

Figure 3.

The train rolls through the green hills and towering palm trees on its

way to Santiago de Cuba.

Figure 3.

The train rolls through the green hills and towering palm trees on its

way to Santiago de Cuba.

The fourth region is the Oriental area. Its major provincias are Granma, Holguín, and Santiago de Cuba (see Figure3). This region is often considered the most impressive of Cuba. It has the swiftest streams, highest mountains, richest mines, and most breath-taking bays. The Sierra Maestra and the Sierra del Cristal cradle this area. Between these mountain ranges, there is a valley that is an economical power. The hills produce nickel, chromium, iron, copper, and manganese. Industry includes mineral processing and electrical power plants.

In 1976, the Oriente provincia was disassembled into Las Tunas and Granma. The area now known as Granma is 3,229 square miles. The deposits from the Cauto River have created plains that are used for growing mangrove. One-third of Cuba's rice is grown in and around the capital city, Bayamo. The provincia provides shoes, chocolate, cigars, canned goods, textiles, lumber, and dairy products. The port city of Manzanillo has a foundry were it processes metal.

Holguín is 3,591 square miles. The Sierra de Nipe and the Sierra del Cristal surround the area. The Salado River runs through the southwest. This area is known as the granary of Cuba. A large portion of the nation's corn and beans are grown here alongside peanuts, sweet potatoes, and cassava. This provincia is also rich in industry. A separating plant for nickel and cobalt, and a processing plant for chromite, are located in Moa. The city of Nicaro has a nickel separation plant along with a foundry for iron and steel.

Santiago de Cuba is another provincia that was created in 1976 with the division on the Oriente provincia. It has an area of 2,382 square miles. The Sierra Maestra stretch along the southern coastline. Cuba's highest elevation, Turquino Peak, is located in Santiago de Cuba. The northern slopes of the Sierra Maestra yield juniper and pines. The southern slopes, however, are arid and produce little of anything. This territory turns out similar products as the other provincias. Santiago de Cuba also produces textiles and furniture.

The last geographical region is actually separate from Cuba. It is the Isle of Juventud. The island was sparsely populated until the 1970's. The Cuban government established resettlement programs to populate the island. The cultivation of citrus fruits supports the island.

Cuba is a land rich in resources and landscape. With varied flora and fauna, it is a wondrous place. From its plentiful mountains to its lovely beaches, there is something for everyone.

The Spanish fortified Havana's valuable harbor against sea attacks from 1567 until 1574. Piracy and buccaneering were profitable at this time. Many great treasures were stolen and hidden in mysterious places; others were taken back as booty to the mother country. In 1628, Piet Heyn attacked a Spanish treasure fleet for the Dutch. Heyn and his crew buried the loot on the island of Cuba.

In 1762, England invaded Cuba. For 10 months the English troops occupied Cuba giving Cubans a glimpse of new commercial opportunities (Wood 74). From this point on, Cuba had a new awareness of the world. Havana looked out into the world to begin a career as a world cosmopolitan city.

Spain continued to rule Cuba, and the colonial government in Spain became increasingly oppressive around 1868. Cuban exile groups living in New York and Florida exploded with animosity towards the mother country Spain.They rose up against the Spanish laws. The Americans saw this reaction and sympathized with the Cubans (Wood 111).

In 1872, José Martí appeared on the scene and formed a party known as the Revolutionary Party. Martí was soon a Cuban leader, and he led the revolutionary War of Independence in 1895. The war lasted three years, taking the lives of over 400,000 people (Chadwick 27-28). Spain responded brutally to the rebellion. General Valeriano Weyler, nicknamed "the butcher," was sent to enforce the new laws. Spain's atrocities brought the U.S. and Cuba closer together (Wood 111).

For the United States, the last straw occurred when the U.S.S. Maine sank in the Havana harbor with a mysterious explosion. As a response to this, the U.S. declared war on Spain; the conflict lasted ten weeks. Oddly enough the Cuban revolutionaries were not grateful for the American help. They were afraid that in the future the U.S. would gain control over them; they wanted to be free. On December 10th the Platt Amendment, a peace treaty in favor of the U.S., was signed. In 1899, the Spanish troops left Cuba forever (Chadwick 30).

The Cuban government acceded to the terms of the Platt Amendment; however, the revolutionaries were irate. The Platt Amendment allowed the U.S. to intervene in Cuban affairs, and establish naval bases on Cuban territory. In 1902, the Navy troops were withdrawn and Cuban was declared a republic.

Gerado Machado came into power in 1925. The Cuban republic was falling apart. Over half of the population was unemployed (Chadwick 37). Machado shut down high schools and universities. He deported and killed many of his opponents. The Cubans were not happy with the way Machado was ruining their republic and, in 1933, he was forced into exile.

Batista y Fulgencio, a sergeant in the army, took over. His army took over the existing Cuban army. He then controlled of the state. He said he didn't want supreme power; rather, he wanted to rule under "obedient" presidents as chief of staff. But, in 1933, he was forced into exile. (Wood 112).

In 1940, Batista was elected president of Cuba. He led Cuba into World War II as an American ally. The U.S. declared war on Germany, Japan, and Italy (Chadwick 39). Because of this action, Batista became exceedingly unpopular in Cuba about the year 1944. He remained president, but he stayed in the shadows. In 1952, he became the dictator of Cuba -- his slogan was "honesty before money" (Chadwick 40). Batista dissolved the Congress and suppressed political parties. Cuba lacked freedom of almost every kind, but still remained extremely prosperous (Wood 112).

Fidel Castro, a trained lawyer, began to hold political rallies in 1953. He became popular because of his radical attitude, anti-imperialist feelings, and anti-capitalist tendencies. Many people came to hear him speak because he was an excellent public speaker. He arranged for a planned attack on the Moncada army barracks. Castro was caught and put on trial. The trial was held in secret because Batista was afraid of the effect of Castro's trial would cause on the Cuban revolutionaries who supported Castro (Wood 112).

In 1954, Batista staged an election. He wanted to legitimize his political position so he held an election against a non-existent opponent. In 1955, Batista freed hundreds of political prisoners; oneof these was Castro. But, Batista government was terrified of Castro's influence and would not permit him to speak publicly. Castro moved to Mexico for a year and a half. While in Mexico, he received money from Cuban exiles living in Florida and New York. He instructed a military cadre and kept in touch with Cuban based revolutionaries (Wood 113).

Castro invaded Cuba in 1956, and it proved to be a disaster. His men were hit hard by the Cuban troops on the Oriente Beach. Only Castro and eleven of his men escaped into the Sierra Maestra Mountains. The Cuban government thought Castro was dead, but in 1957 Herbert Matthews (of the New York Times) found him. Matthews wrote many favorable stories about Castro; this increased U.S. sympathy, thus causing Castro to become publicly known. Batista was scared when he realized that Castro was still alive and planning a revolt. Batista increased oppression.

Fidel Castro launched another attack in 1959, and, this time, he was victorious. After Castro slaughtered Batista's men in Havana, order in the government was instantly restored. Castro triumphantly march to the capital to claim his victory. He had the growing support of Cuban revolutionaries. Castro went from revolutionary to a reformer and took control.

Castro embraced the philosophies of Marx, creating a socialist nation. He developed relations with Soviet Union and eventually began to force communist dogmas on the Cuban people. This affected some harder than others. The lower class was just happy to finally have an equal portion of land and work. The upper and middle classes became outraged at their loss of land and property. Many of them left the country for the U.S.

Castro seized U.S. holdings in Cuba because he disliked the presence of the U.S. in Cuban affairs. The large agricultural estates were divided, and land was given to peasants. Castro declared that 66 acres was the "vital minimum" for a family of five.

The U.S. gave Russia an ultimatum in 1963 to pull their troops out of the country. This compliance with the U.S. soured Russian-Cuban relations,and Castro then turned to Red China for help. Through this, Cuba lost much of their militancy. By the year 1966, Cuba had a shortage of supplies and an overflow of political prisoners in the Cuban jails. Regardless, Castro was stronger than ever. The Cubans were satisfied because they owned property, and they felt that Castro cared about their needs (Wood 114).

In the early years, Castro did very well and was exceedingly popular with the general public. He guaranteed the people prosperity and protection. He was an intelligent man and an excellent talker. He told the people everything they wanted to hear. The Cuban economy was getting back on its feet. Land was divided so that people without land would be able to farm. Job positions opened, and the Cuban people were beginning to feel a sense of confidence in the government.

Many new laws came into effect. Castro began to rule as a dictator. He tortured and executed those who did not agree with his philosophies. Small rebellions have broken out in Cuba. Castro sees these as a threat and tries to break down any anti-government activities. He regulates all media, radio, newspapers, and even art forms. The Cuban people have no individual freedom to do and say as they please.

Of course, there are people in Cuba who are happy with the present day socialist government. Many of Castro's followers still love him because they feel that he has done a great deal of good for their country. He has raised the literacy level, provided important social services, and helped the economy. Others, however, wish Castro had never come into power. Since the revolution, thousands of Cubans have migrated to the U.S. to escape Castro's rule. The Cuban-Americans have gotten legislation passed that ensures Cubans an immediate occupancy in the U.S. The U.S. has not yet intervened militarily but has placed an embargo on Cuban goods.

Currently Cuba is categorized as a unitary socialist republic with one legislative house. The head of state and of the government is President Fidel Castro. The island is broken up into 14 political districts --Camaguey, Ciego de Avila, Cienfuegos, Ciudad de La Habana, Granma, Guantanamo, Holguin, La Habana, Las Tunas, Matanzas, Pinar del Rio, Sancti Spiritus, Santiago de Cuba, and Villa Clara. There is one individual muincipality (the Isle of Youth) and 169 other municipalities. The political system is broken up in political associations, associations and state organizations, and state institutions (Mastrapa section 1).

The political associations function as the political vanguard of the people's political sub-system. In this political organization, there are two main sections: Partido Comunista Cubano (PCC), the Cuban Communist Party and its organization for the youth of the republic, the Union de Jovenes Comunistas (UJC) or Communist Youth Union. These sub-systems include Leninist design, selectivity of membership, class distinction, and programmed discipline (Mastrapa 1).

The state association is the governmental assembly in the republic. The sectors of the state associations include National Assembly of the People's Power, Council of Ministers, Revolutionary Armed Forces, and organizations which carry out institutional justice (one such organizations is the Council of the State). These organizations are the governing bodies of the Republic of Cuba and make and enforce the laws (Mastrapa 1).

Right now in Cuba there are three main political parties which can be found in the government : the hardliners, the centrists, and the reformers. The first is the hardliners, led by Fidel Castro; this one prohibits any kind of liberalization (political or economic) from forming in the republic. The second is the centrists, led by Racel Castro (Fidel's brother), which acts to provide security among issues and promote modest economic reform. The third is the reformers, led by Foreign Minister Roberto Robaina and Economic Czar Carlos Lage, which tolerates and helps work out problems with loyal opposition (Mastrapa 2).

In 1990, the revenue was CUP 12,463,200,000. The expenditures were CUP 14,448,400,000 which included: capital investment 37.7%; education and public health 20.4%; social, cultural, and scientific activities 17.3%; defense, internal security 9.5% (Britannica 2).

The land of Cuba is extremely fertile; thus, agriculture is a major industry. Sugar is, by far, Cuba's largest industry. The country's economy is dependent on the sugar industry. Cattle farming is also a profitable for the Cuban economy. The cattle graze on the natural grassland which covers Cuban soil.

In 1996, the production rates were as follows: (in metric tons) 40,000,000 sugarcane; 364,000 potatoes; 291,000 oranges and tangerines; 261,000 grapefruit; 260,000 bananas; 250,000 cassava; 223,000 rice. The livestock numbers were 4,650,000 cattle; 1,500,000 pigs; and 19,000,000 chickens (Britannica 2).

Foreign trade is vitally important to Cuban economy. In 1996, the total amount of imports in U.S. dollars was $3,010,000,000). The 1992 figures breakdown s follows: 39.4% in mineral fuels and lubricants, 25.4% food and live animals, 15.8% machinery and transport equipment, 6.9% chemicals, 6.6% basic manufactures, and 3.2% crude materials. Cuba's major import sources are Spain, Canada, Russia, Mexico, France, and Argentina (Britannica 3).

Export is also important to Cuban economy. In 1996, the total amount of exports in U.S. dollars was $1,831,000,000 . The 1992 figures are as follows: 63.4% sugar, 10.6% minerals, 5.9% fish products, 4.6% tobacco products, and 3.4% citrus. Cuba's major export destinations include Russia, Canada, the Netherlands, and China (Britannica 3).

Tourism is also a source of income to the Cuban economy. In 1995, the receipts from tourists totaled $1,100,000,000 in U.S. dollars. Fidel Castro was quoted as saying, "we still have an awful lot to learn about tourism; it will be the leading industry." Tourists come to Cuba to see the beautifully exotic natural wonders. The main source of attraction is Varadero Beach. This 20 kilometer beach is known for fine white sand studded with palm trees and surrounded by the transparent sea. Guama, a restored Taino Indian village, is the second major tourist attraction. This village is built on piles in a lagoon, making it extraordinary. The third main tourist attraction is the Isle de la Juventd, noted for being the site which inspired Robert Louis Stevenson to write Treasure Island. The isle encompasses many natural caves, favorite hide outs for long ago pirates and corsairs.

Most of the work in Cuba is done in factories and out in the fields. The women work in the factories and the men travel around trying to find work in a field or in construction. Almost all of Cuban labor is in the form of manual labor. The pay is very minimal, leaving most Cubans in a state of poverty.

The Confederation of Cuban Workers is the only labor union. This is due to the fact that Castro will not allow other labor Unions to exist; it does not function on the Western model because there is a shortage of skilled labor in Cuba (Britannica2 1).

Women do not expect the men to provide for them. The women of Cuba work hard to support their families. Incomes for most women do not pay enough to support a family. Work is hard for the mothers. It pays little and includes no benefits. Many families are poor and struggle to have enough food to eat. In the latter part of the 20th century, women have started to form labor unions and fight for higher pay, better working conditions, and better housing. This has been a hard fight, however, they are beginning to see results. Co-ops have been started and women receive housing with some jobs. In the past, Cuban women were sheltered in a male centered social order, but, today, they are replacing men in factories and in government positions more and more frequently.

Women are well represented in the labor force and a sex education program has been implemented, both created to promote equal rights. Several organizations have been developed in Cuba to help demand equal rights. Unfortunately, most Cuban women see these mass organizations such as Committees for the Defense of Revolution (CDR), Youth Organization (UJC), and Women's Organization (FMC) as simply another political party rather than autonomous organizations designed to provide assistance to meet their demands. These groups continue to develop over time. Changes are not taboo and in the mass organizations there are open discussions about the failing of the revolution to meet the women's needs. The FMC is slowly but surely responding to the various issues brought out by the Cuban feminist movement.

From 1492 to 1898, the country was a Spanish colony. The country was used as an administrative center for Spanish political and economic control of the region. Most of the population, and economic, and political growth was in the city of the Havana. Because of this the economic growth of the eastern regions was very restrained, and there was less opportunity for this side of the country to progress even in the post-colonial period.

In 1959, the year of the Revolution, the urban literacy rate was high by the Latin Americans standards, however, the literacy rate countryside was very low. A very vigorous campaign began to teach the rural population how to read and write Spanish. With this program Cuba accomplished a lot and it got much recognition throughout the world.

In 1991, almost half of the Cuban population of 10.7 million was under the age of 30. This was related, in part, to the emigration of more than one million Cubans to other countries because of the Revolution. The population in Cuba is approximately 51 percent mulatto, 37 percent white, and 11 percent black and 1 percent Chinese. About 40 percent of the population lives in the western side and the major urban areas like Havana, Matanzas, and Pinar del Rio. Twenty percent of the population lives in the provinces of Villa Clara and part of the western Camaguey. Another 20 percent lives in northwestern Santiago de Cuba.

Since the period of the Spanish colonial the rural population has migrated to cities like the Havana, Matanzas, and Santiago de Cuba. After the Revolution in 1959 a lot of efforts were made to make them go back to the country side and slow down the migration to the cities. Even though the population growth in Havana declined, the urban population did not: 62 percent of the women and 58 percent of men lived in the cities.

Before the Revolution, rural homes of the poor, particularly in the mountainous regions, were constructed from palm thatch, cane, and mud with dirt floors. These bohios traditionally dominated the countryside around sugar cane fields and family subsistence farms. They are only gradually being replaced with partially prefabricated cement multifamily houses. There have been several cycles of construction, but they have not kept pace with housing needs. In the urban centers, housing combines single family Spanish style architecture, low rise apartment units, single story apartments joined in rows, and, in the oldest cities, some former single family homes have been converted into multiple units. The Spanish patio arrangement is more predominant in the older houses.

The revolutionary Cuba society has been trying to eliminate the racism and sexism. With the mix combination of races like the Spaniards and other western Europeans, Africans slaves, and Chinese, Cuba's Latin African mulato culture shows less racial tension than racially separated societies. The revolutionary government keeps trying to integrate and give power to the women and to the Afro-Cubans.

The kinship ties and social ties of the Cuban upper class were based on the descent from the Spanish colonial aristocracy. The ability to keep family backgrounds and share the names and saints became less significant after the Revolution of 1959. The lower classes continued with the Latin traditions such as godparenting and maintaining close relationships with the extended family.

In pre-Revolutionary Cuba, the church played a very important part in society. Marriage and baptism assumed more importance in the cities than in the countryside. After the Revolution both rates of marriage and divorce increased. The marriage rated declined a little in the late 1970's. Postmarital residence was patrilocal.Extended families are found in forty- percent of Cuban households. Different types of birth control were used, including abortion.

Efforts have been made to strengthen family solidarity and stability, as well secure female equality. The Family Code at1975 called for equal sharing of responsibilities in domestic work. There was also a mandate for child-care centers to reduce gender inequality and modify traditional gender-defined roles.

Catholicism has always been the principal religion in Cuba. But there are also other religions such as Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian. Some researchers say that the Catholic Church does not have as much influence as in other Latin American countries because of the separation between religion and the revolutionary government. Afro-Cuban Santeria, is a religion that is derived from the African slaves and is a mix of Yoruba and Catholic culture heritages. It is deeply engrained in Cuba Culture and has the respect of the people and other religions.

Under the revolutionary government, Cuba made a lot of changes. The

number of libraries has grown from 100 to 2,000 and museums from 6 to 250.

There are also many workshops and institutes for music, dance, theater,

art, ceramics, lithography, and film which are housed in 200 casas de cultura.

New schools of film industry have produced international works and several

publishing houses. Political poster art, street theater, and experimental

workplace theaters have been appeared in the revolutionary period. The

Afro-Hispanic cultures, including the traditional folk or guajiro song

and dances, have been emphasized since 1959.

The first definitive step in musical nationalism in Cuba was taken by Ignacio Cervantes (1847-1905), who was the most important composer of his generation. He was a student of Gottschalk and Ruiz Espadero and then of Marmontel at the Paris Conservatoire and had a great career as a concert pianist. Many of his works combined with folk-music elements of Afro-Cuban and guajiro traditions in a Romantic virtuoso piano style.

Later distinguished composers associated with musical nationalism included Amadeo Roldan and Alejandro Caturla; both found "Afrocubanismo" the most appropriate source of national expression. The stylistic idiosyncrasies of Roldans are best seen in his series of six Ritmicas in 1930 for various instruments. Caturla had some of his works published in Europe and the USA. His gifted and original treatment of Afro-Cuban Music is well represented by his La Rumba in 1933 and Tres Danzas Cubanas in 1937 for an orchestra, and particularly by his many settings of Alejo Carpentier's and Nicolas Guillen's Afro-Cuban poems. For some time Roldan was the leader of the Havana PO, founded in 1924 by Pedro San Juan. Before that, the Havana PO had been under Gonzalo Roig, composer of the popular zarzuela, Cecilia Valdes.. Ernesto Lecuona, a member of the same generation, was internationally distinguished for his musical comedies and several popular songs.

After the premature deaths of Roldan and Caturla, Jose Ardevol held the position of composer and teacher from the 1930s to the middle of 1950s. He gave many young composers a solid technical training, and he established the Grupo Renovacion Musical in 1942 in Havana, a group that favored contemporary music. The group's manifesto states, however, that a "national factor is indispensable in musical creation, in the sense that all artistic expression within a cultural setting" (Behague and Borbolla 1995).

Little is known about the folk music of Cuba before 1800. A couple of conclusions can be made from early descriptions of the island's indigenous music from archaic instruments such as maracas, large conches, and wooden drums. It is thought that the music that Columbus brought only vaguely influenced folk musicians. The archives of Hernando de la Parra talks about a music which used the violin, clarinet, violon, which is a large guitar, and vihuela. A lot of this music was played by Micaela Gines, who was a liberated slave from Santo Domingo. Laureano Fuentes (1825-98) recorded that in1580, Santiago had only two or three musicians, all of whom had belonged at one time to the organization of Teodora and Micaela Gines. One of the best known early tunes from Cuba was La Ma-Teodore, which was named after Micaela's sister. Nevertheless, the tune has many elements common in 16th century European folk songs; it has a simple structure, and close links with some ecclesiastical forms.

Another early example of Cuban Folk music was San Pascual bailon and El sungambelo. These are referenced for the first time by Ramirez; however, their written style clearly belongs to that style at the beginning of the 19th century, the musical language of the coteries of the Cuban salons.

The traditional music in Cuban culture has its roots in African heritage. These musical traditions have helped keep the people of Cuba aware and appreciative of their beginning; the culture of Africa can be observed in Afro-Cuban music.

Rumba, which can also be spelled rhumba, is one of the most popular forms of Afro-Cuban music (Cuba[EBO] 1). The word "rumba" comes from the verb "rumbear" which means going to parties, dancing, and having a good time; rumba basically means to party. Rumba music is extremely rhythmic; the musicians can use anything from sticks, bottles, and cardboard boxes to more expensive drums (Durr 1).

The African roots of Cuban music can be most clearly observed in this style of music; originally, it was played on streets corners by neighbors who just wanted to get out and "party." Poor urban sights, commonly found near sugar refineries, are the home to these neighborhood parties (La Rumba 1).

The rumba dances are supposed to be erotic and enticing; originally meant to be a marriage dance (Dance R). The two most common forms of rumba are columbia and guaguanco; these sub-genres are played (and danced) in a 2/4 meter (Durr 1). The columbia is performed by a solo male dancer; the dance is fast and synchronized precisely with the drum beat. The dancer's moves are short, aggressive, and acrobatic (Durr 2). The guaguanco is a slower form of the rumba, and it is performed with a man and a woman. This dance, which is one of the most popular dances in Cuba, demonstrates the woman's pursuit by the male partner. The man uses parts of his body to entice the woman; therefore, this dance is extremely erotic, especially when the man does the "vacunao" or thrust of the pelvis (indicating penetration) (Durr 2).

The guaguanco is usually performed on the drum trio: tumbadora, segundo, and quinto. The quinto is a set of sticks which is used to play the 3/2 "rumba clave," sometimes as a featured solo. The drums (tumbadora and segundo) carry out the 2/4 meter of the song (Pertout 1Guag).

Rumba became extremely popular in the U.S. in 1933 as a ballroom dance. The steps are similar to that of the guaguanco dance, although the U.S. version is not nearly as erotic as originally performed in Cuba. The dance is performed in 4/4 time, which is different than the Cuban 2/4 meter (Rumba[EBO] 1). The basic movement can be described as "two quick side steps and a slow forward step, while keeping the torso erect." The movement described has become known in the U.S. as the "Cuban Motion" (Dance R).

Son is the other most common Afro-Cuban music and is informally known as Cuba's national music and dance. Some claim that rumba is a sub-genre of son, while others feel that they are two separate genres of Afro-Cuban music. Regardless, son has definitely been the most influential style in Latin American music.

The origin of son dates back to the Spanish-descended farmers and their slaves in the late 1800's. This music is a combination of instruments and poetry and was commonly performed by black and mulatto musicians. Traditional subjects of son were love, humor, and patriotism; newer themes include social and political views. The lyrics of son are composed in a "decima" or ten-line, octosyllabic verse (Durr 2).

The son meter is also performed in 2/4 time. The son clave has a reverse and a forward clave. The forward clave is a bar with three notes and then a bar with 2 notes; the reverse clave consists of a two note bar followed by a three note bar (Pertout 1Clave). The three note bar is strong and is called the tresillo; the two note bar is a weaker version of the tresillo (Durr 2).

The song part and the estribillo or montuno section are the two parts which compose the music of the son. The montuno part is the most important section in the son; it contains the singing (both choruses and solos) and musical improvisations. Some of the instruments which play improvisations are the tres (a three doubly stringed guitar), bongo, bass, and trumpet (Durr 2). Many contemporary dances have evolved from the son, most importantly the mambo, the salsa, and the cha-cha, all three of which are 20th century ballroom dances (Dance S).

Danzon is another traditional Afro-Cuban musical style. It was developed in the 1870s in Matanzas, one of the "cradles" of African-based folklore in Cuba. Many Africans were brought there as slaves and their descendants have preserved their African traditions to the present through various forms of African folklore.

The dance of the danzon is a very slow, elegant dance performed by couples. The dance itself was first danced January 1, 1879 in the "Licea Artistico y Literario de Matanzas" (Cuba Danzon 1). The music is different than any other type of Afro-Cuban music because it is played with instruments like the flute, piano, and strings, the style is very classical sounding. The danzon is considered the aristocratic dance of Cuba because of the dignified and elegant appearance of the dancers.

In November of 1998, Cuba Danzon, a festival to celebrate over 100 years of danzon music in Cuba, was held in Matanzas. This was the second Cuba Danzon to be held. The groups which performed were as follows: Alturas de Simpson, Fefita, Almendra, El Cadete Constitucional, La Flauta magica, El Bombin de Barreto, Rompiendo La Rutina, and Angoa. Participants in the festival were involved in danzon competitions, and received prizes for the best dance (Cuba Danzon 2).

The influence of traditional danzon can also be heard in the U.S. In San Francisco, a group called Orquesta la Moderna Tradicion can be found playing the local music scene. This group is headed by Robert Borrel (Cuba Danzon 1).

Another festival celebrating the traditional music of Cuba was the Percuba festival, held in Havana April 13-17, 1999, at the Cuba at Casa de la Cultura de Plaza (Percuba 1). This event showcased traditional and concert percussion styles, and featured concerts, colloquia, contests, workshops, video presentations, and displays of instruments. Participating in this event were 400 Cuban performers and 40 guest members from 22 countries outside of Cuba (Percuba 1).

Grupo AfroCuba is a Matanzas-based group which performs a variety of traditional Afro-Cuban music. Their success is evidence that the people of Cuba still enjoy the traditional sound of music. The goal and ambition of Grupo AfroCuba is to preserve the musical aspects of African heritage, and to introduce African heritage to new audiences (The Story 1).

AfroCuba was initially named Guaguanco Neopoblano and was founded in 1957 to play drum-chant style rumba. In 1968, they recorded under the name Folklore Matancero, and, in 1973, changed their name to Grupo AfroCuba. When they changed their name for the final time, they publicized their ambition "to preserve the African traditions of Matanzas and bring them to the attention of the rest of the world."Francisco Zamora Chirino, the group's artistic director said, "Our goal is to keep the legacy of our ancestors alive, while enriching it with our creative interpretation" (The Story 1).

In 1952, Carlos Puebla formed a group called Los Tradicionales. They are recognized for playing traditional and folk music, and perform regularly at a cafe in Havana called the Bodeguita del Medio. The group is especially popular with students and young revolutionaries who enjoy the traditional sound of the music (Los Trad. 1).

Los Tradicionales is an internationally recognized group, traveling throughout Europe and Latin America. Although the group is no longer headed by Carlos Puebla, who retired in 1988 due to illness, the group is still a huge success. The group is now headed by Octavio Abreua, who added Fidelena Ceballos Reyes, the first female voice to join the group (Los Trad. 1). Afro-Cuban music is a very important tool in keeping the society aware of their heritage. The music is still revered and enjoyed by the people of all ages.

Drums

Figure 4.

Bongo drums.

Figure 4.

Bongo drums.

The bongo (see Figure 4) is a small, wooden double-drum that is played with the fingers. The heads, which are 5 inches and 7 inches around, are turned apart from each other. The heads are usually tuned a fifth apart at the notes C and G ("bongo drum," 1). The bongos were initially used for playing son. Originally, the bongo heads were tacked in place. They were then tuned by using a heat source to stretch the hide. The modern day bongo was introduced in the 1940's. Metal tuning lugs were placed around the edge of the head to make tuning easier (Trevor Salloum & Eric Stuer, 1). A seated musician, called a bongocero, rests the bongo on his or her calves. Much of what the bongocero plays is improvised. The rhythm of the bongo is often used as a counterpart to the main drum pattern.

Figure

5. Conga drums.

Figure

5. Conga drums. Figure 6.

Timbales.

Figure 6.

Timbales.

Timbales (see Figure 6) are a percussion set-up that has two small metal drums. The practice of adding cowbells and cymbals began in the 1930's. The bells are tuned to different pitches to add a variety of sounds. Unlike the bongos or congas, the timbales are played with sticks instead of the hands. The timbales are also called the pailas (Herman, 2). The timbales were created to provide a more portable drum. The timpani was too large to be moved. The drums are usually tuned to specific notes and then changed between songs.

The Batá drum is a direct descendant of the drums used by the Yoruba tribes in Africa. It is a double-headed hourglass drum with laced heads. Sometimes the one head of the drum will have bells attached to it (Marcuse, 46).

Rattles, Scrappers, and Claves

Figure 8.

Guiro and cabasa in a tambourine.

Figure 8.

Guiro and cabasa in a tambourine.

Two of the instruments pictured here (see Figure 8) are the guiro and the cabasa. The guiro, also known as a guayo or rascador, is made from a gourd that has notches cut into it (Sadie, 86). A singer plays it by running a stick along the notches. The construction of a cabasa is a bit more complicated than that of the guiro. The center of a cabasa is made from a steel cylinder. Strings of steel balls are then wrapped around the cylinder. The cabasa is held in one hand while the steel cylinder is rotated in the other.

Figure

9. Maracas.

Figure

9. Maracas. Figure 10.

Shekere.

Figure 10.

Shekere.

The shekere (see Figure 10) is another instrument derived from African origins. A shekere is made by taking a large gourd and stringing a net of beads around the outside. It works on the opposite idea of the maracas.

Figure

11. Claves.

Figure

11. Claves.Two pieces of resonant wood are struck together. The preferred wood is cocabola (Marcuse, 111). These instruments are more common in traditional Cuban music than modern music. Claves have very specific patterns for different types of music.

Other Instruments

The tres is a small guitar. The name derives from the original idea that the guitar had three, tres, metal strings (Marcuse, 531). The modern version has nine strings. The tres became very important to the Cubans living in New York in the 1960s and 1970s.

Figure 12.

Marimbula.

Figure 12.

Marimbula.

The African slaves introduced the mbira to Cuba and, over the years, it was transformed into the marimbula (see Figure 12). However, the marimbula is tuned to lower pitches than the mbira. The marimbula is made of a small wooden box with metal prongs attached to it. It is approximately 60 cm in size (Sadie, 617).

The cencerro is a large cowbell played with a stick, which can produce

two distinct tones depending on where it is struck (Glossary, 2). The cencerro

is most often used for congas or rumbas.

The mambo is a dance which originated in the Haitian settlements of Cuba. The dance of the mambo is not found in Haiti, although Haitians brought the dance to Cuba. In Haiti, a voodoo princess is referred to as the Mambo (meaning conversation with the gods); she is the village counselor, healer, exorcist, soothsayer, spiritual advisor, and organizer of public entertainment (Barendrecht 1).

The music of the mambo has both African and European characteristics. The European influences can be traced back to the seventeenth century dances, including England's country dance, France's contredanse, and Spain's contradanza. These European influences later arrived in the eighteenth century in Cuba becoming known as the danza and eventually becoming the national dance.

In the nineteenth century, the European influence was left behind as the music became freer and more spontaneous, evolving into the Cuban danzon. This type of music was full of improvisation solos featuring a variety of instruments such as the cello, piano, guiro, clarinet, and flute.

In the 1920's, a lighter version of the danzon became known as charangas. In 1938, the first mambo was composed; it was actually a danzon written by Orestes Lopez which he titled "Mambo." This song included elements of both the danzon and the son, another popular traditional Cuban music form (Leymarie 1).

Although it was Orestes Lopez who first came up with the mambo, it is Perez Prado who created the mambo dance and introduced it in 1943 at La Tropicana, a night club in Havana (Barendretch 1). Prado's compositions were the first ever to be marketed under this genre. The difference between his mambo style and the existing danzon style was the jazzier feel. Prado used jazz instruments and drums more than traditional instruments. This musical style was a mixture of swing and traditional Cuban music. Two of Prado's most famous dance numbers include "Patricia" and "Mambo No.5," both of which were recorded in the early 1950's. Isabelle Leymarie, author of Mambo Mania, said that these two songs "took Latin America and the United States by storm" (Leymarie 1).

It didn't take long for the mambo to make its way to the States. Shortly after the mambo was introduced to Cuba, the mambo was seen in the Park Plaza Ballroom, a New York dance club. In 1947, the mambo was becoming increasingly popular at renowned places such as the Palladium, the China Doll, Havana Madrid, and Birdland (Barendretch 1). Dancers who joined in the obsession of the mambo were called "Mambonicks." Although mambo took the United States by storm, it died out almost as quickly as it came. Today, the only people who really dance the mambo in the U.S. are professional and advanced dancers. The mambo has been considered to be one of the hardest dances.

The mambo is played like a rumba only with an improvisational ending. Rather than the 4/4 meter of the rumba, the improvisational riff was played in a 2/4 meter, with the emphasis on 2 and 4. The mambo dance is performed as type of "offbeat" rumba. The foot patterns and dance steps are described as follows: This dance ignores the "1" count of each measure, using the "2-3" for the rock steps. "1" is generally a pause step, unless otherwise noted (like the kick).

Recently, the mambo has made a comeback to the U.S. thanks to Eddie Torres, a New York dancer, who has appeared in several films while dancing the mambo. He is known as the "Mambo King of Latin Dance." Mambo is still very popular in Cuba. The Cubans enjoy dancing the mambo at parties and community get-togethers; they also listen to the music of the mambo as it continues to grow and evolve into new forms of music.

Dr. Morton Marks writes of other influences to salsa. Afro-Cuban rhythms from bebop jazz, the mambo, salsa conjuntos, charangas, Puerto Rican plena and bomba music, and the bugalu all helped to shape salsa (5). These musics continually mix and flow together to enrich the total musical base.

Although the term salsa is characteristic of a Cuban style of music, the term actually originated in New York City. Cuban and Puerto Rican immigrants living in New York coined the term around the 1960's. The dominant record companies and clubs were located there, including the record label Fania. This label helped to launch salsa into the limelight of New York and then the world.

The man most associated with salsa is Arsenio Rodríguez, a famous big band leader in the 1940's. He is credited with combining musical styles and instruments from Cuba with the brass sections of American swing bands (Weldeghiorghis, 1). He also reincorporated African roots into the music. Other bandleaders include Machito (Frank Grillo), Tito Puente, and Perez Prado. Many of these were regulars at the Palladium Theater in New York City.

The term salsa became a marketing tool in the early 1960s. The tag was used to lump all Latino music into one category. Some Latinos saw this as the popular white majority's way of suppressing the Latino culture (Manuel, 46). Many Latinos rebelled against the North American exploitation of Latino culture.

Major record companies and independents were vying for control of salsa. Manuel, in his essay, writes that not only was salsa used as a commercial vehicle, it was also a form of social identity; and the two were inseparable (163). As salsa became more popular, the music industry fought to inoculate the political and social commentaries that were contained therein. As Manuel says, the record companies were trying to sell "ketchup rather than salsa" (163).

Salsa instrumentation is similar to the other types of Cuban music. There is a strong percussion section consisting of congas, Batá drums, timbales, and claves. Brass, lead guitar, and bass are also popular additions. The claves beat out a regular rhythm of either three-two (see Figure 13) or two-three (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.![]()

Robert Doerschuck has commented on the importance of the piano in salsa music. He writes, "Unless [the pianist] understands the style, with its complex vocabulary of syncopations, alternating linear and chordal passages, and modal solo lines, the groove may never get off the ground. In salsa, the tiniest nuances can be crucial" (313). Although the claves may help to keep the rhythm going, the piano, in salsa, is the root of the beat. The piano serves as a percussion instrument in salsa, rather than a melodic one.

![]() Figure 15.

Salsa dancers.

Figure 15.

Salsa dancers.

Salsa is not just a type of music; it is a type of dance. To truly understand salsa, one must be familiar with the salsa as a style of movement (see Figure 15). The salsa is a dance for couples, with either an open or a closed posture. There are also a number of "figures," or more difficult steps and variations involved in the salsa. These figures consist of turns, twists, and solo parts. These figures are more popular with the European dancers than the traditional Cubans.

While New York was the birthplace of salsa, its ties to Cuba are undeniable. The music has grown as a marketing tool and a link to ethnicity. As a dance form, salsa has grown and penetrated many other countries including Germany, Denmark, and Japan. Salsa will continue to expand and disseminate as long as there are people who want to dance the night away.

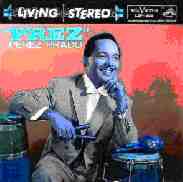

He is better known as El Rey del Mambo, or king of the Mambo. He was born in Matanzas, Cuba on December 11, 1916. When he was a child he studied classical piano at the Principal School of Matanzas and also as a young man he played the organ and piano in cinemas and clubs. Around 1941, he moved to the Havana and played piano for the Orchestra del Cabaret de la Playa de Mariano. He changed jobs playing piano for orchestra like Orchestra Cubaney and Orchestra Paulina Alvarez. Prado also wrote some songs for these orchestras. Since he was so talented, one of the most popular orchestra at the time hired him as a pianist and the arranger.

Prado began to develop the conception of mambo in 1943. He said that the mambo came out of after hour sessions when musicians would sit around and play their instruments. The rhythms that were mixed resulted in mambo. Perez describe mambo as an Afro-Cuban rhythm with a dash of Americans swing. According to Prado the mambo has more swing than the rhumba and also more beat. Prado calls himself "a collector of cries and noises, elemental ones like seagulls on the shore, winds through the trees, men at work in a foundry." To many Perez Prado was the creator of the mambo.

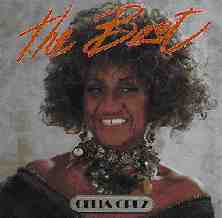

Celia Cruz

Celia Cruz was born in a humble town of Santo Suarez in Habana, Cuba; she was one of the 14 children. At home, she used sing to his brothers and sisters, and the adults used to gather around to listen to her sing. As a teenager, she began singing in school programs and community gatherings. Many times, her aunt took her and her cousin to sing in cabarets and nightclubs where the talented singer got a first hand view of the local talent. While the rest of her family supported her musical abilities, her father encouraged her to continue her studies and become a schoolteacher. However, it was one if her professors who told her to take chance on the music because it would take her a day to make what he earned in a year.

Celia Cruz began entering the local radio talent shows winning fancy cakes and more opportunities to compete and sing with the popular orchestras of the time. Her big chance came when in 1950 when the popular Sonora Matancera took on an unknown and slightly rough around the edges Celia Cruz.

The popular group was known and loved throughout the country. However, the public was not used to seeing new talent with the orchestra that it did not recognize. Thus, Celia did not fare well in the beginning. The public began calling the radio complaining about the new singer. Also the executives did not believe that female singers could sell albums. But, the band believed in Celia; members thought she had the inspiration and the swing.

Her perseverance overcame the obstacles, and Celia eventually became permanent in the orchestra. She traveled with the orchestra throughout the Latin America and Mexico, staying with with the band for about fifteen years. She and the band became know as " Café con leche" (coffee and milk).

By 1960s, Celia Cruz left Cuba permanently to pursue a career in the United States. She became a permanent citizen in 1961 with a contract to perform in Hollywood Palladium. It was during that time that she felt in love with Pedro Knight, the first trumpet in the orchestra. By 1962, they were married and by 1965, he took a step back from his career to manage that of his wife whom he adored.

In 1966, she combined forces with Tito Puentes and recorded eight albums with him for Tico records. However, the power of these two great musical legends was too much for the public to handle, and record sales did not reach expectations.

By 1974, Celia was riding a tide success. She hit the market hard with a concept album in which she teamed with Jonny Pacheco. His love for Afro-Cuban and charange rhythms made him an innovator producing updated arrangements of classic tunes. Celia and Jonny went gold. Salsa was re-born and Celia was on her way to becoming its most shining star. After two more record breaking hits with Pacheco, Celia sang with the Fania All-Stars, an orchestra composed of band leaders signed with the label. She traveled on a international tour with the group that covered London, England, Cannes, France and Zaire. She has traveled through all of Latin America; she has recorded some twenty gold LPs and won more than a hundred awards from various institutions, magazines and newspapers. She appeared in a special segment of the Grammies in 1987 where she performed with her old time collaborator, Tito Puentes.

The magic of Celia Cruz has won her global recognition, and numerous tributes. She has a Yale University doctorate, the admiration of her peers, a Hollywood star, a Grammy, a statue in the famous Hollywood wax museum, the key to numerous cities, and the key to the hearts of Latin music lovers everywhere.

AfroCuba Matanzas is one of the most popular folklore groups in Cuba. They perform traditional African dances, percussion, and songs. The company was found in 1957 in the city of Matanzas, also known as one of the cradles of Afro-Cuban folklore. There, many of the centuries-old African-based traditions have been maintained in their purest form.

AfroCuba is recognized throughout the world because of their full spectrum of Afro-Cuban folklore. The groups members are not just great musicians; they are also practitioners of the religions whose music and dance they perform. Their instruments have been hand crafted using the old methods and original materials, making for an authenticity of sound.

Their music is also Influenced by Spanish flamenco and the secular rumba. AfroCuba presents the three variations of rumba.. The yambu is played on wooden box drums know as cajones, highlighted by the sensual movements of a couple dancing. The guaganco, which is a wonderful interaction between the competitive spirits of the two dancers. The woman, prancing seductively, connotes the symbolic gesture of sexual possession. The columbia, a competitive solo dance for men, is a raw display of masculine prowess characterized by sharp athletic movements and precise interplay between the dancer and lead drummer.

AfroCuba has performed extensively to great acclaim throughout Cuba and worldwide. In 1989 they mesmerized audiences at the Smithsonian Institute's Folk Life Festival in Washington, D.C.

Ibbu-Okun (River & Sea)

Ibbu-Okun, is an all female Afro-Cuban folkloric group. The group was formed in Havana in 1993 and performs a repertoire Afro-Cuban music and dance traditions such as palo, yuca, arara, iloosa; and various styles of rumba like yambu, guaguanco and columbia.

Amelia Pedroso is the Ibbu-Okun's founder and director. She is a highly respected percussionist, singer, teacher and performer of Afro-Cuban ritual traditions. For more than 20 years, she has taught and performed as a singer and master percussion on stage, television, radio and records. Pedroso and the other members of Ibbu-Okun are participants in Afro-Cuban ritual life for which music plays a fundamental role in communicating with the deities and for whom the drum is a voice. Raised during the period of social change, the women of Ibbu-Okun challenge the stereotype that only males can play the drums. Women have traditionally been denied access to the Bata drums. But, as drummers, they were drawn to the challenge of learning the language of the Bata. On stage the women of Ibbu-Okun have demonstrated their musical ability and versatility.

Behague, Gerald, and Carlos Borbola. "Cuban Folk Music," In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Stanley Sadie, editor. London: Macmillan Press, 1984.

Blades, James. Percussion Instruments and their History. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1970.

Castro, Fidel. History Will Absolve Me. Bungay, Suffolk (GB): The Chaucer Press, Ltd., 1969.

Chadwick, Lee. Cuba Today. Westport, CT: Lawrence Hill and Company, 1975.

Davis, Darien. Slavery and Beyond: The African Impact on Latin America and the Carribean. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1995.

Doerschuck, Robert L. "Secrets of Salsa Rhythm: Piano with Hot Sauce." In Salsiology: Afro-Cuban Music and the Evolution of Salsa in New York City, Vernon W. Boggs, editor. Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1992.

Manuel, Peter. Popular Musics of the Non-Western World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Manuel, Peter. "Salsa and the Music Industry." In Essays on Cuban Music, Peter Manuel, editor. Maryland: University Press of America, Inc., 1991.

Marcuse, Sibyl. Musical Instruments: A Comprehensive Dictionary. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964.

O'Connor, James. The Origins of Socialism in Cuba. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1970.

Randall, Margaret. Cuban Women Now. Toronto: The Women Press, 1974.

Sadie, Stanley, ed. The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. 3 vols. London: Macmillian Press Limited, 1984.

Wood, Peter. Caribbean Isles. New York: Time Life Books, 1975.

"Brief History of Cuba (April 7, 1996)." 25 February 1999. http://www.fiu.edu/~fcf/histcuba.html.

"Cienfuegos and Villa Clara Provinces." 24 February 1999. http://library.advanced.org/18355/cienfuegos_and_villa_clara_pro.html.

"Cuba Danzon." 7 April 1999. http://afrocubaweb.com/FestivalDanzon.htm#announce.

"Cuba Photo Gallery." Photographs by Joe Raedle. 19 February 1999. http://sun-sentinel.com/news/Cuba/photogallery.htm.

Dance Dictionary. March 16, 1999. http://www.arthutmurray.com/.

Duante Management. "Celia Cruz, The Queen of Latin Music." 28 April 1999. http://www.ejn.it/mus/cruz.htm.

Dürr, Petra. "Afro-Cuban Rhythms and Dances." 22 April 1999. http://www.latin-dance.de/Music/p-dances-petra.html.

Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

"Bolero." http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topic?eu=82624&sctn=1&pm=1.

"Bongo drum." 17 March 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topice?eu=82750&sctn=1&pm=1.

"Camagüey." 13 February 1999. http://www.rb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/99/34.html.

"Cauto River." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/110/77.html.

"Ciego de Ávila." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/128/40.html.

"Cienfuegos." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/128/43.html.

"Cha-cha." http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topic?eu=22538&sctn=1&pm=1.

"Conga." http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topic?eu=26251&sctn=1&pm=1.

"Cuba." http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topic?eu=127844&sctn=4.

"Cuba." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/152/82.html.

"Cuban solenodon." 18 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topic?eu=70356&sctn=1.

"Granma." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/243/65.html.

"Guaniguanico, Cordillera de." 13 February 1999.

http://www.eb..com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/249/47.html.

"Havana." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/262/26.html.

"Holguín." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/274/36.html.

"La Habana." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/333/14.html.

"Las Tunas." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/339/30.html.

"Maestra, Sierra." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/366/48.html.

"Matanzas." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/380/66.html.

"Mambo." http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topic?eu=51632&sctn=1&pm=1.

"Physical Map of Cuba." 19 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topic?bin_id=5206.

"Pinar del Río." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/468/4.html.

"Political Map of Cuba." 19 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topic?asmbly_id=8862.

"Rumba." http://www.eb.com:180/bol/topic?eu=66069&sctn=1&pm=1.

"Sancti Spíritus." 13 February 1999. http://www/eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/523/85.html.

"Santa Clara." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/525/22.html.

"Santiago de Cuba." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/525/90.html.

"Solendon." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-gin/g?DocF=micro/555/46.html.

"The West Indies." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=macro/5006/64/23.html.

"Villa Clara." 13 February 1999. http://www.eb.com:180/cgi-bin/g?DocF=micro/623/50.html.

"Farmer at work in Pinar del Río." CUBA, Portrait of a Nation: Photo Collection. 19 February 1999. http://www.cubanet.org/fotoindex.html.

Fernando, Sylvia."Grupo AFROCUBA de Matanzas" (August 13,1996). 24 February 1999. http://metalab.unc.edu/mao/musicians/afrocubamore.html.

Flawith, Vikki. "Ancient Music Comes to Life." 30 March 30 1999. http://www.grannyg.bc.ca=faith=ancient.html.

Glossary of Latin Musical Terms. "Afro-Cuban Jazz Explosion!" 16 March 1999. http://www.upo.com/fullpower/glossary-of-terms.htm.

Herman, Nick. "History of Afro-Cuban Percussion Instruments and Their Use in Cuban Popular Music." 16 March 1999. http://www.quimbombo.com/percussion.htm.

"Ibbu-Okun (River & Sea)." 28 April 1999. http://metalab.unc.edu/mao/musicians/ibbu_okun.html.

"La Rumba de Cuba." 16 March 1999. http://www.columbia.edu/~alt12/Drums/rumba.html.

"Latin Percussion: Bongo Drums." 17 March 1999. http://www.mhs.mendocino.k12.ca.us/MenComNet/Business/Retail/Larknet/LatinPercussion.

Levy, Joseph. "Perez Prado and Mambomania (1995-1997)." 28 April 1999. http://catalog.com/arts/prezbio.htm.

Leymarie, Isabelle. "Mambo Mania." 16 March 1999. http://catalog.com/arts/mambo.htm.

"Los Tradicionales de Carlos Puebla." 30 March 1999. http://putumayo.com/cd/coffee/coffee.html#los.

"Marimbula." Latin Rhythms -- Instruments. 31 March 1999. http://www.cam.org/~raybiss/rhythms/instrum.html#bata.

Marks, Morton. "The Evolution of New York Salsa Music." 22 April 1999. http://members.aol.com/SalsAleman/orisalsa.htm#Son1.

Mastrapa, Armando F. "Government and Politics of Cuba, 1998." http://polisci.home.mindspring.com/cuba_government.html.

"Percussion Source -- Castanets, Guiros, Jingle Bells, Maracas, Claves, & Cowbells." 31 March 1999. http://www.westmusic.com/ps/psaux1.htm.

Pertout, Alex. "Clave Concepts; Afro Cuban Rhythms." 16 March 1999. http://www.netspace.net.au/~pertout/lclaveac.htm.

Pertout, Alex. "Congas." 16 March 1999. http://www.netspace.net.au/~pertout/congas.htm.

Pertout, Alex. "Guaguanco: Afro Cuban Rumba." 16 March 1999. http://www.netspace.net.au/~pertout/lguaguanco.htm.

"Queen of the Guiro." 31 March, 1999. http://www.sonic.net/~roadman/bloodnotes/sw10-98/guido/.

"Rhumba." 29 April 1999. http://www.zem.co.uk/dance/rumba.htm.

Salb, Maria, Lisa. "Afrocuba de Matanzas (1996)." 28 April 1999. http://www.dcci.com/cuba_arte/afrocub1.htm.

Salloum, Trevor and Eric Stuer. "Bongo Drums: History." 17 March 1999. http://rhythmweb.com/bongo/history.htm.

Shekere. "Percussion Instruments." Latin Rhythms -- Instruments." 31 March 1999. http://www.cam.org/~raybiss/rhythms/instrum.html#bata.

Singer, Roberta. "The Cuban Son and New York Salsa." 22 April 1999. http://members.aol.com/SalsAleman/orisalsa.htm#Son1.

Tapia, Ariel. "The Son Never Left Cuba." Cuba Press (January 8,1999). 31 March 1999. http://www.picadillo.com/vgdesign/articles/901081.html.

"The Principal Church in Sancti Spíritus, Las Villas." CUBA, Portrait of a Nation: Photo Collection. 19 February 1999. http://www.cubanet.org/fotoindex.html.

"The Story of AfroCuba." 30 March 1999. http://www.shanachie.com/Artists/grupoafrocuba/history.htm.

"The Timbales (Les Timbales)." 31 March 1999. http://www.salsa.media-site.com/anglais/aTimbales.html.

Weldeghiorghis, Ermias Kebreab. "Salsa.." 22 April 1999. http://www.reading.ac.uk/~aarwldhs/salsa.html.

Top